The Linear B exhibition at the Stephen Lawrence Gallery has been curated and created around the principle that each artist’s exhibited work takes inspiration from an artwork in the collection of the late artist Nikos Alexiou. What emerges are a whole series of other connections that can be seen in the work to other artists, as each individual forms a dot on an interconnected spider diagram across which you could trace connections similar to the idea of the six degrees of separation through which you should be able to link to anyone on the planet through someone you know knowing someone that knows someone, etc. I wonder how many steps would be statistically necessary to link two seemingly unconnected artists. Much as Mafalda Santos in her installation Cross Reference (2011) at The Mews Project Space has drawn out her social network across the walls and ceiling of the gallery leaving a remnant of chalk dust on the ground like the fallout from broken friendships. Occasional lines that were probably accidentally drawn at the wrong angle due to not having a long enough ruler peter off half way like a relationship that has not yet been made or has been cut off, the blue chalk slightly rubbed away as the memory fades.

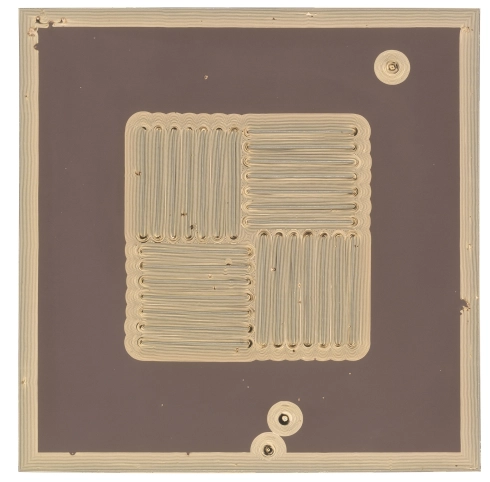

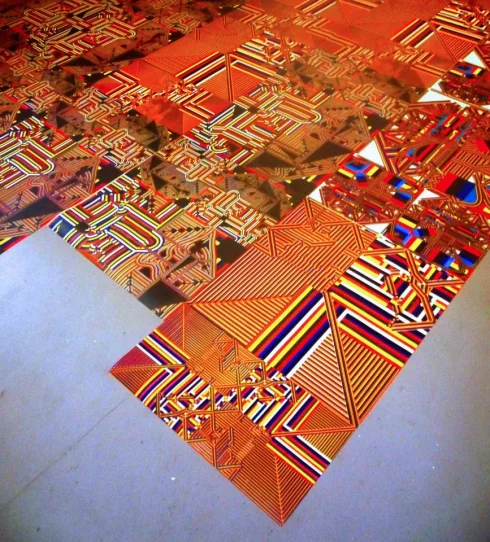

Plans for a New Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (detail) (2011) by Jonas Ranson, silkscreen print on paper.

In Linear B Jonas Ranson’s Plans for a New Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (2011) is made in response to Vassili Balatsos’ perspective drawing of, or design for, a modern minimal building, clad in industrial metal strips and with a balcony on the upper floor, made with strips of primary coloured tapes. However whilst Ranson picks up using parallel lines in a mixture of primary colours, this large print also seems to heavily reference Pierre Cordier’s Chemigrams featured in the V&A‘s Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography exhibition last winter. Cordier created a photographic technique he called Chemigram, painting materials such as nail vanish and oil onto photosensitive paper prior to exposure and developing. The traces left from painting, as in Chemigram 30/12/81 I (1981), leave a perfect series of parallel lines created by the brush stroke, an abstract composition which could perhaps depict cornfields with neatly arranged rows of crops. These marks are much like the parallel lines in Plans for a New Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (2011), which appear to describe buildings, roads, paths, corridors or electrical circuit diagrams, that map a building, campus, development or city, just as Balatsos’ drawing maps a building and records the parallel vertical lines of its cladding.

In turn it feels like Cordier’s work could have influenced some of Bernard Frize‘s abstract paintings. Whilst Ranson has produced a print and Cordier has worked with photography albeit in a painterly fashion, Frieze frequently paints bold, sweeping, continuous lines, which similarly retain the marks of a wide brush.

Meanwhile Cordier’s Chemigram 7/5/82 II “Pauli Kleei ad Marginem” (1982) has been linked to referencing Paul Klee‘s Ad Marginem (1930), which seems to depict the sun surrounded on all sides by birds, flowers and abstract figures, who could be worshipping it. However, due to its triangular centre this reminds more of the classic album cover for Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon by Hipgnosis and George Hardie (1973), with some edges perhaps bitten by snakes ala the computer game, whilst the curve cornered straight forms reflect upon the shape of the extending character.

Across these three media we find aesthetics that function similarly across these art forms, with both linear order, aligned with architecture and planning regulations, and the unpredictability of human interaction and nature.